Reflections on victimhood: A psychodynamic perspective

I recently came across an article examining the psychology of victimhood, specifically through the construct referred to as the Tendency for Interpersonal Victimhood. The article itself was clear and accessible. What held my attention, however, was not the novelty of its claims but the way they intersected with questions I have been considering in my clinical work for some time.

In recent months, themes emerging from my correspondence and from broader cultural conversations have led me to look more closely at self-pity, internal conflict, and how suffering becomes organized within the personality. Read in this context, the article served as a reminder of how easily such dynamics can be simplified. It also underscored how closely the so-called “victim position” is bound up with these questions, particularly when approached from a psychodynamic perspective.

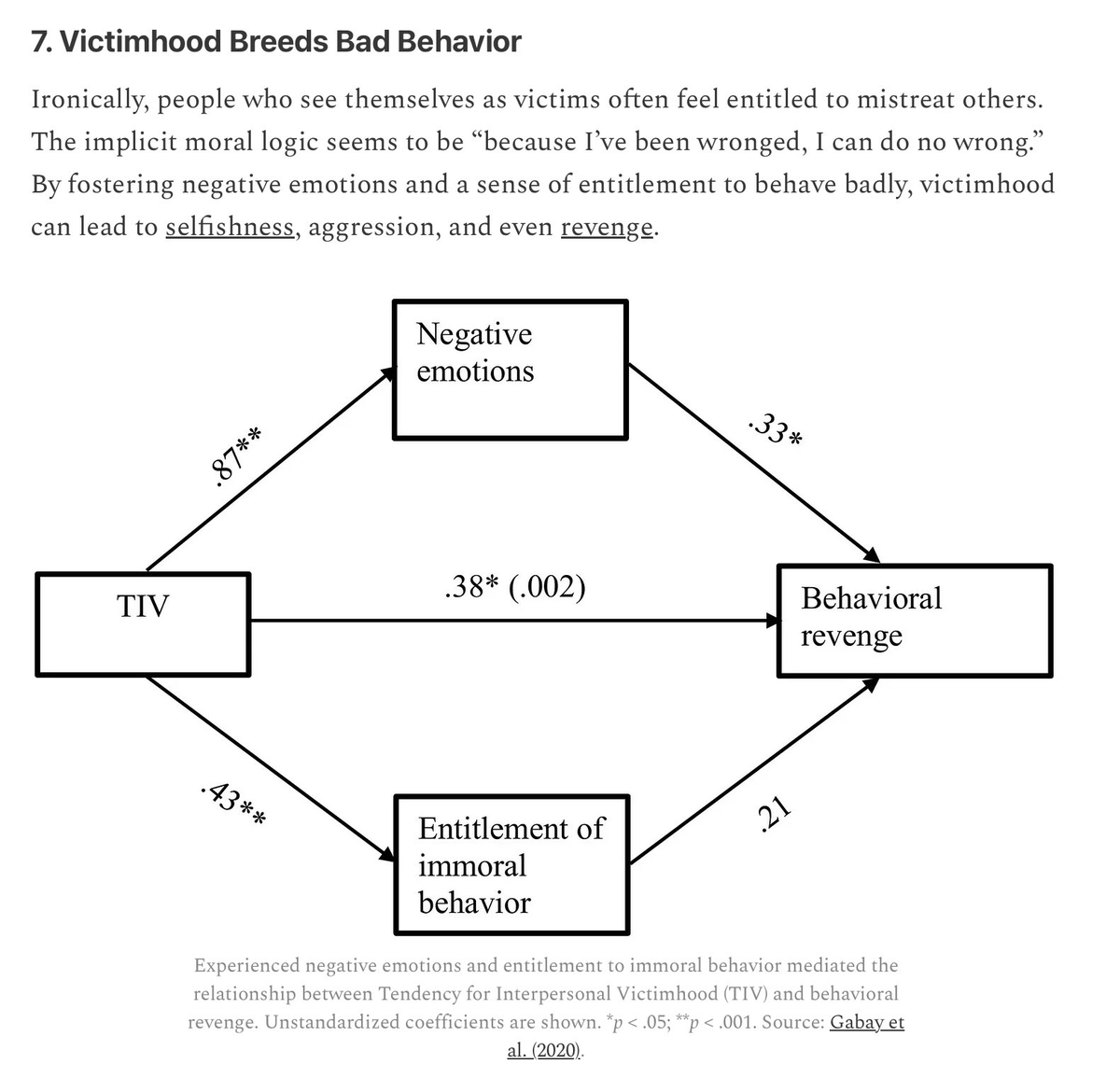

The article suggests that chronic identification with victimhood is associated with intense negative emotions, a sense of moral entitlement, reduced empathy, and, at times, retaliatory behavior. Empirical research supports these observations. As a psychodynamic clinician, however, I find myself less interested in confirming that these patterns exist and more interested in understanding why they persist so strongly in certain individuals.

From a psychoanalytic standpoint, victimhood is rarely just a conscious attitude or strategy. More often, it reflects a deeper internal organization. Freud observed that experiences of injury, particularly narcissistic injury, tend to weaken internal moral restraints and intensify aggression. Melanie Klein described psychic positions in which individuals experience themselves as persecuted and morally blameless, with aggression toward others feeling justified or even necessary. Otto Kernberg later showed how recurring grievance and entitlement can become structural features of certain personality organizations, rather than situational reactions.

Seen this way, victimhood functions less as a claim about reality and more as a psychic coping mechanism. It can serve as a shield against unbearable feelings of guilt, shame, or helplessness. Winnicott would remind us that when early emotional support is insufficient, a sense of being wronged may help preserve continuity of the self. Letting go of this position too quickly can feel neither relieving nor safe.

What I found missing in the article was this developmental and relational dimension. When victimhood is framed primarily as a personality trait or moral stance, its defensive function can easily be overlooked. In clinical practice, this distinction is crucial. There is an important difference between recognizing how victimhood shapes behavior and reducing it to manipulation or bad faith.

From both a psychodynamic and ethical perspective, the task is neither to confront victimhood directly nor to reinforce it uncritically. Rather, it is to understand the psychic work it performs, the pain it contains, and what might become possible if that pain can gradually be thought about rather than acted out.

I share these reflections not as a rejection of psychological research, but as an invitation to deepen it. When empirical findings are held together with psychodynamic understanding, the picture becomes more complex and, I believe, more humane.

References

-

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. London, England: Heinemann.

-

Freud, S. (1914). On narcissism: An introduction. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 67–102). London, England: Hogarth Press.

-

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and its discontents. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 21, pp. 57–145). London, England: Hogarth Press.

-

Gabay, R., Hameiri, B., Rubel-Lifschitz, T., & Nadler, A. (2020). The tendency for interpersonal victimhood: The personality construct and its consequences. Personality and Individual Differences, 165, 110134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110134

-

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York, NY: Jason Aronson.

-

Kernberg, O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

-

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27, 99–110.

-

McWilliams, N. (2011). Psychoanalytic diagnosis: Understanding personality structure in the clinical process (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

-

Ok, E., Qian, Y., Strejcek, B., & Aquino, K. (2021). Signaling virtuous victimhood as indicators of Dark Triad personalities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(6), 1634–1661. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000329

-

Stewart-Williams, S. (2025, June 21). 12 things everyone should know about the psychology of victimhood: The strange allure of being wronged. Substack.

-

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. In The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development (pp. 140–152). London, England: Hogarth Press.

© 2025 by Shabnam Sadigova

Table of Contents